Basics of Shell Scripting

This article is Part 1 in a 4-Part Series.

- Part 1 - Basics of Shell Scripting

- Part 2 - Shell Scripting Constructs

- Part 3 - Process Management and Job Control

- Part 4 - Shell Functions

It’s no secret that the use of Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs) has become so ubiquitous that nowadays, using the command-line is regarded as some sort of arcane skill reserved only to those who have devoted themselves to the dark arts. But this doesn’t have to be the case. And although there’s no question about the convenience brought by GUIs, if you want to leverage the power of your OS you have to be comfortable using the shell.

So, what exactly is a shell?

Simply, a shell is a program that provides users with direct OS interaction via inputs usually from the keyboard. In the early days of computing, this is the only means you have to interact with your computer. Often, words like terminal, console and tty are used interchangeably with shell but they all have special meanings.

Originally, a tty (shorthand for teletypewriter), is a particular kind of device which resembles a typewriter that is used to input commands into the computer. In unix terminology, however, tty is used to refer to a device file1. A terminal, in its most common meaning is closely related to tty. It is a session which can manage input and output for command-line programs. The console, on the other hand, is a special case of a terminal, the other being a terminal emulator.

Shell Comparison

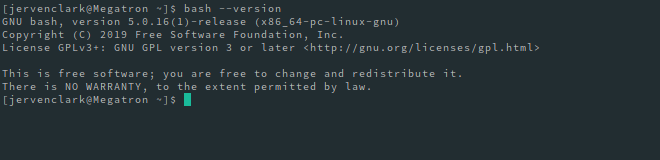

One of the major shells used in early UNIX systems was a shell program called Bourne Shell. This was developed by Stephen Bourne at Bell Labs in the 1970s. It provided users with a rich set of utilities. It is represented by the dollar $ command line prompt. In most systems, the Bourne Shell is named sh usually found at /bin/sh but a number of compatible work-alikes are also provided with varying degrees of added improvements and features. For instance, in my system, the sh program is a symlink to **bash, Bourne Again Shell, which is a superset of the Bourne Shell in terms of functionality.

The following is a non exhaustive comparison of various popular shells

| Feature | Bourne | C | TC | Korn | Bash |

| Aliases | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Command-line editing | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Advance pattern-matching | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Filename completion | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Directory stacks (pushd and popd) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| History | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Functions | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Key binding | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Job control | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Spelling correction | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Prompt formatting | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

The syntax of all these shells is 95% similar.

Getting our way around the terminal

Let’s get started by opening a terminal and type in:

$ echo $SHELL

be sure to only copy the commands after the dollar sign. This will then output something like:

/bin/bash

From here on, we will use the word shell to mean bash and if we mean any other shell, such as zsh, we will specifically mention it by its name.

The following table lists a few basic Linux commands:

| Command | Description |

| ls | checks the contents of the directory |

| pwd | used to check the present working directory |

| mkdir new_folder | used to create a new directory called new_folder in the current directory |

| cd new_folder | used to change the working directory to new_folder |

| touch new_file.sh | this command creates a new empty file new_file.sh |

| cp new_file.sh file_2.sh | this command copies new_file.sh to file_2.sh |

| mv new_file.sh file_1.sh | renames new_file.sh to file_1.sh |

| rm file_2.sh | removes the file named file_2.sh |

| rm -rf new_folder | removes recursively the contents of new_folder |

Writing our first script

A shell program, or shell script, is a collection of a series of commands for a UNIX shell. No separate compiler is required to execute these scripts as the shell itself interprets and executes each command one line at a time.

It has serveral advantages over compiled programs such as:

- easy to write and run

- easy to start since no additional setup tools are needed

- very handy and convenient saving development time

- easy to debug

Let’s start by creating a new file called hello.sh

$ touch hello.sh

Put in the following lines:

#!/bin/bash

# This is a comment line

echo "Hello, World!"

Let’s breakdown the following lines. The first line is called a shebang line which is used to call the intended shel, in this case, bash. This should always be the first line in the script. The next line is a comment. It is ignored by the shell and is used to annotate your scripts. The last line is an echo command which will print “Hello, World” onto the screen.

To execute this, we can do either:

$ bash hello.sh

or

$ chmod +x hello.sh

$ ./hello.sh

The first way is pretty straightforward - we are essentially telling bash to execute the file hello.sh. The second way involves adding an executable flag to the hello.sh then running it as an executable file.

When not to use a script?

Given the many advantages of a shell script, there are also a few limitations that we should keep in mind.

- every line in a shell script creates its own process in the operating system which makes it slower than compiled programs

- not very suitable for heavy math calculations

- problems with portability

- manipulating and generating graphics is very limited, usually we can only use printable symbols as graphics.

Notes

-

a device file is an interface to a device driver that appears in a file system as if it were an ordinary file ↩